Producer Eddie Kramer along with filmmaker John McDermott held an interview with Q104.3 to discuss Jimi Hendrix’s last studio album released in 1968 “Electric Ladyland”. Kramer also mentions his meetings with The Beatles and Led Zeppelin.

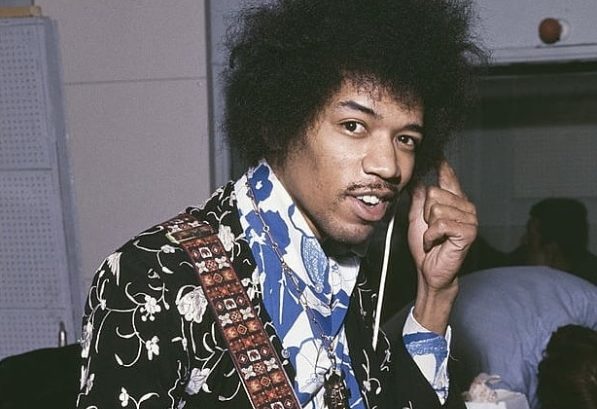

Photo Credits: YouTube /

Q1043 New York

I want to start up by clearing up some info for me. This album was or was not recorded at what is now known as ‘Electric Ladyland’ on West 8th Street in Manhattan.

Eddie: “That is incorrect. This album was recorded – it started in England actually, at Olympic Studios in London in late 1967 early ‘68.

“I moved to America, I came in to specifically continue work with Jimi. I was invited by [producer/engineer] Gary Kellgren who’d just built the Record Plant – that’s the studio 321, West 44th Street, and that’s where I landed to continue working with Jimi.

“Gary has been in the studio with Jimi for like a month or so, and then I arrived in April and we continued working.

“Some of the tracks for ‘Electric Ladyland’ were actually cut at Olympic, like ‘All Along the Watchtower’ for instance. Now there’s a story about that… ”

We want to hear that story. Jimi played bass on that song actually, right?

Eddie: “He certainly did, because Noel [Redding] went to the pub and got drunk, I think.”

That’s shocking to hear. Getting back to the ‘Electric Ladyland’ – the studio itself, what is the background of that studio? I always heard or read that the ‘Electric Ladyland’ studio was a part of a record deal for Jimi with Warner Brothers Records.

“Jimi wanted to build a nightclub basically – the old – generation night club. He was jamming there for about six months and the club closed, and then it was for sale, and then Jimi and his manager brought it.”

To this day, it’s an active studio, one night I’ve gone to like a Gary Clark Jr. listening party, and then the next night, like Mumford & Sons in there mastering their record or something.

“It is still an existing studio, it’s still one of the greatest studios in the world and it’s been going almost 50 years now.”

Lots of special guests on this album, [Traffic’s] Steve Winwood, [Traffic’s] Dave Mason, [Jefferson Airplane’s] Jack Cassidy… Stephen Stills, I think, plays on it too. How did these guests appear at those sessions? Was it very informal, was it planned out, did you get a phone call? How does that work?

Eddie: “Well, imagine that you’re on the 44th, and two blocks away is this famous nightclub that Jimi used to go jamming, called The Scene.

“Jimi would be there from like 8-9 or 10, we’re sitting in the studio, everything all set up, we’re ready to go, all the mics are checked out, he comes strolling in at midnight dragging behind him 20 people.

“Imagine him walking down the 8th Avenue stopping traffic – that’s a big scene – comes in the studio, dragging in Steve Winwood, Jack Cassidy, whoever, couple rehearsals, one take, two takes, maybe, and there’s ‘Voodoo Child’ done, finished, thank you very much, live from the floor, there it is.”

So at what time would you get to the studio?

Eddie: “We’re there at seven, and we’re sitting until the next morning at seven.”

So, Eddie, you were with them for this album, you had already worked with him a lot at this point, and knowing that he was breaking so many barriers musically, culturally, I’m just wondering as an engineer, how do you tell Jimi to take another take on a song? ‘Hey Jimi, that was great but, you know, why don’t you try that again?’

Eddie: “Jimi, would you mind taking that again? ‘Yeah, yeah yeah, no problem man,’ That’s what it was like.’”

But he was notorious for taking like 20 takes, right?

Eddie: “Well, that was part of the modus operandi for Jimi. I mean, he could sometimes get a vocal in a couple of takes, but he was very much of a perfectionist. Same thing with the guitar. Occasionally, he’ll get it in one or two takes, but most of the time – ‘Hey man, I got to do it again.’”

So, for the crazy guitar freaks out there like myself – when Jimi got a guitar to play, it was a right-handed guitar. What did he do? He turned it over, did he restring it, how did he do it?

John: “Yeah but, you know, Jimi was kind of an off-the-rack guy. He wasn’t somebody who was really precise. He would go to Manny’s and get like a white Strat or black Strat and you know, do exactly that.

”Just take a Strat, turn it over, restring it, and play. He wouldn’t play it upside down like Otis Rush or Albert King, so he would restring it, but I just think that he was somebody that was able to make things happen with it with a very simple setup.”

So, at this point in Jimi’s career, had he really developed and matured as a songwriter?

John: “Yeah, [manager] Chris Chandler helped him. Chas is really the hero of the Hendrix story in a lot of ways. He saw it, he had the big picture vision. He understood Jimi’s talent.

“If you think about Chas, he’s been the bass player in The Animals, they’d had like, 10 Top 40 hits, he understood the commercial pop market, so I think his skill as a producer was to continue to refine Jimi, put some parameters on him, to say, ‘Here’s what you got to do, you got to write more, you got to focus more on crafting the song.’

“I think by the time that he came to ‘Electric Ladyland,’ it was really a marriage of Chas’ influence, really great-constructed pop songs, like ‘Crosstown Traffic,’ with things like ‘Rainy Day Dream Away’ which is one of my favorites.”

Eddie: “Chas was the guy. In the beginning, when Chas and Jimi lived together, Chas was the one who’d set up with him, ‘Come on man, you got to write some songs.’ London, ‘67 in the very beginning.

“They shared a love for science fiction, comic books, that’s where a lot of these influences came from. It was Chas saying, ‘Jimi, you got to write, you got to write’ because when he first started, he was doing cover songs.”

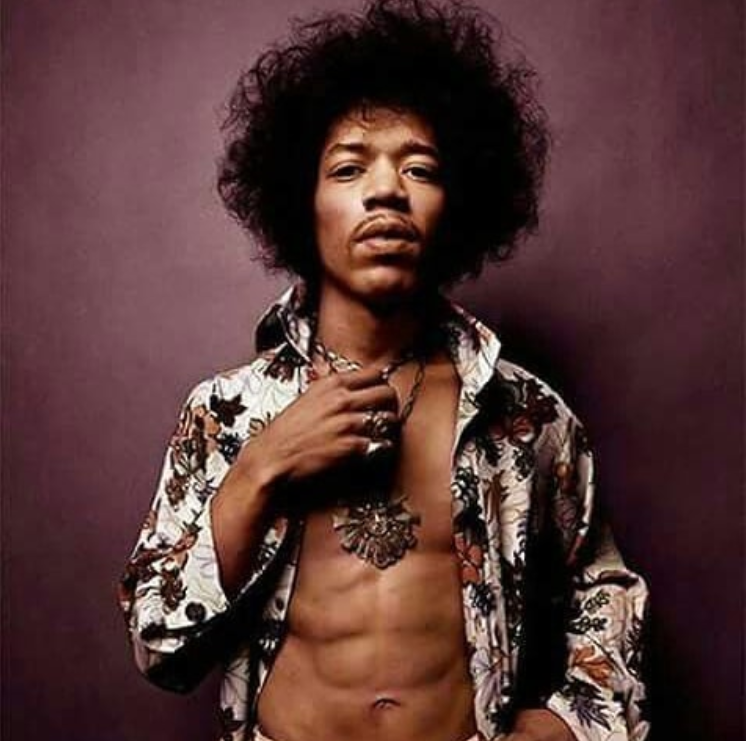

Photo Credits: Instagram / gimmehendrix

Big hits on this album, we’re talking about ‘All Along the Watchtower,’ ‘Voodoo Child,’ ‘Crosstown Traffic’…Tell us a story about ‘All Along the WatchTower.’

Eddie: “We started the track in London at Olympic and there were a couple of very interesting moments during the cutting of that track.

“I remember very clearly that Jimi was quite uptight with not only Mitch [Mitchell], but Dave [Mason], because he couldn’t the ‘quing-quing’ sound – all that Dave had to do is play the open chords and just strum across the strings.

“So once they got over that and they figured out, ‘Okay, this is how we’re gonna do it’ – we were about to take deep into it, and all of a sudden I hear this really horrendous piano ‘clang- clang,’ playing the wrong chords all out of time, and it’s Brian, he had slipped into the studio and he’s completely out of his mind.

“So he comes in and he sits in front of the console, we took 23 takes, we got the master, and I turn around, he’s up, he’s gone to sleep, he’s out, and that’s it. The ‘All Along The Watchtower’ four-track was brought to America and transferred to 12-track, and then Jimi said, ‘Oh man, eight more tracks, woo-hoo, can I add eight more tracks of guitar?’”

Both of you talk about the amount of unreleased music live or studio that was out there, scattered around the world after Jimi died. When you look at this relatively short career, you look at these 3-4 years and it seems like he was either in the studio recording, or he was out there performing live. I hear these stories about tapes in studios, all over the place, talk about that…

John: “I think what’s interesting – you got to understand in Jimi’s life he had been denied the ability to record, he was this kind of the itinerant side for Little Richard and the Isley Brother, and when the few times he would get to record, he would be told specifically what to do and was not allowed to kind of put his own shine to anything.

“So I think by the time [Chas] Chandler gave him the gift of opportunity, he ran with it. He didn’t have 15 cars, he wasn’t into that. What he did, he put his money into a recording studio. It’s still here today, if he had never made another record after 1970, he’d still be running the studio and be successful.

“That was his passion, and I think he had a relationship with Eddie that was very supportive.”

Eddie, when people ask you about your work with Led Zeppelin, is there one story that comes to mind immediately? An anecdote?

“Yeah, the recordings. Led Zeppelin at Mick Jagger’s house called Stargroves in England. There was a song called ‘Black Country Woman,’ and the boys decided that they wanted to record the Christie guitar basic track outside on the lawn.

“We had the Stones’ mobile truck parked outside, and as Rober’s [Plant] doing the vocals, and this bloody great big four-engine airplane passes right over. Airplane engines going over, and I hit the talk-back but I said, ‘We rub it, what about this airplane?’… ‘Nah, leave it’. And that’s actually on the CD, that’s when they cut that right in.”

I want to ask you the same about The Beatles, I think you engineered or worked on ‘All You Need Is Love’?

Eddie: “Well, they booked Olympic studios because they couldn’t get into EMI, and I was the lucky one who was the engineer to work with them. They come in and John [Lennon] sits right next to me and he’s got his acoustic guitar, says ‘Come on guys, we got to do this song for TV.’

“And he goes, ‘All you need is love,’ he starts strumming the guitar, and I’m thinking ‘Bloody hell, how am I going to get that vocal through the headphones?’ Because they, the boys all started to walk out into the studio.

“McCartney picks up a bass, Sir George Martin goes over to the harpsichord…so I figured out how to patch that talkback mic into the headphones and he sat right next to me while the song was going, and we grow one reel of tape, which is about half an hour, bomb, into record, here we go.

“They did this about 20 times, get to the end of the roll of tape and he says, ‘Right, coming in, let’s have a listen.’ We wind back to from the end, play it back, ‘Yeah, that’s great, see you later, bye.’

“And they took that half-inch tape to EMI, and that’s what they used to overdub, and then they played that back live through by the TV broadcast. That’s the story.”